The Draugr

2350 words — 12 minute read

fantasy, high fantasy, norse mythology

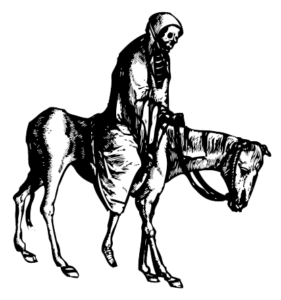

The draugr rode down the road, a winding trail among barren hillocks and rocky outcrops. He was a pale thing, long since dead, his name forgotten. The horse he rode carried him still, as she had since the day they both died.

‘Where do you think the road takes us today?’ the draugr asked. ‘The wind is blowing east, but the road is going west.’

The horse did not reply. She never did.

Once upon a time, there had been settlements in these lands. People had lived in the valleys and the fjords, which were green then. A harsh land, but fertile enough for the stubborn folk of the north. Now only lichen grew on the grey rocks, and no living creature had set foot here in a human lifetime.

The road trailed downhill, between ridges and cliffs, in hairpin turns down the mountainside. Far below lay the fjord, grey and dull under the ever-cloudy sky. The draugr studied the curves and shapes of the mountains and their steep descent into the water.

‘Have we been in this fjord before, Horse?’

At this, Horse raised her head and stared across the valley with empty eye sockets.

‘I don’t recognise that precipice,’ he told her. ‘Or that curtain of a waterfall.’

A new fjord. Was that possible? He had travelled these lands for many lifetimes and thought he had seen every crag and crevice. The road looked the same as any road. Horse continued her steady walk. The draugr shrugged and let himself be carried, down and down along the mountainside.

Hours later, they reached sea level. The sun had set but light still lingered, the clouds only a deeper grey. Had the wind not been the same freezing gale that had blown for years beyond counting, the draugr would have called this ‘summer’.

On their left, the fjord spat white-edged waves onto the shores. Narrow and winding, the road sat precariously on the scree between the steep cliff side and the hungry, salty teeth that bit into the land. Deep crevices cut into the bedrock beside him, foaming white streams rushed down ravines, and while none of that was out of the ordinary, he did not recognise these particular rocks and brooks.

Horse walked on; her hooves steady as always.

Night was short this time of year. Though darkness lurked in the shaded crevices, light never quite left the sky. The two travellers made themselves comfortable and proceeded to stare into the dusky greyness.

Morning had begun to ease the shadows out of the black palette and into the grey, when out on the fjord, a shape emerged. Curves and angles that first appeared to be parts of waves or the shore far beyond, gradually made up the bow of a ship.

‘Horse,’ the draugr said. ‘Do you see that?’

Horse said nothing. But the draugr recognised the ship; torn sails and rotten planks. As the vessel swung around and set course towards the sea, he got the confirmation he had not needed. The rear half of the ship proved to be missing.

‘Well, this is odd,’ he said.

The draugr and his mount had not met another creature for generations. For more years than their lifetimes combined, he and Horse had travelled the land. The sea was not theirs, but the fjords and the coast were. And never, since their deaths, had they seen the ship.

The last time the draugr had seen the ship, he had been thirty-two years old and alive.

A blue plague had come first and stolen the newborn, the elderly, the sickly and the hungry. A blood cough had followed and taken the young and strong. When the harvest failed, people did not wait to starve through the winter, but sought the deep water and the seaweed hands of death. And when the sea winds beat snow and ice all the way into the core of the land, even the wild beasts and the trees and the grass laid down and died.

The half-ship had foretold death then. His brother’s, his wife and children’s, his own. The death of his people and the land itself.

Whose death did the ship foretell this time? What was left that could still die?

The vessel faded into the greys of the fjord, disappearing as mysteriously as it had appeared. The draugr sat motionless for a time, looking at the white-capped waves where the ghost ship had been.

They resumed their descent down the unknown fjord. The road wound and curved around the cliffs and sloping ridges of bedrock that rooted the mountain in the deep water.

He had seen a draugr, too, once, in his youth. Years before he first sighted the ghost ship, one awful day in his twenties, the creature had ridden through the village. People had fled, and livestock, too. The local witch alone had stood outside her hut with a wooden ladle, cursing from a distance, crippled by age, unable to challenge the rider.

She warned the people, afterwards, that the draugr would bring death. But years passed and nothing happened. The villagers stopped worrying. Only after the witch had died from old age had the sickness come.

He had not known Horse back then. She was a riderless mount he had picked up after his family had died, when he started on a hopeless quest for escape from the horrors behind him. He had died days later, and so had Horse.

Once the shreds of dawn had dissolved into the bleakness of day, light changed very little. Around noon Horse’s hooves found soft ground; gravel and sand in banks that might once have held farms and fields with people and cattle.

‘This is unusual,’ muttered the draugr.

More and more of the barren, grey rocks gave way to soft sand — even mud. The stiff wind carried a scent to his nose, familiar but absent for so long he could not place it. Curiosity drove him forward. Still he saw no end to the fjord; no glimpse of the vast sea.

They rode on, and with every hour, the air warmed a little and the wind diminished a little. Rich, earthy smells filled his senses and brought back memories from a childhood and youth long gone. In the late morning they passed between a vertical cliff wall and a boulder the size of a house; a gate, made by the mountain itself.

On the other side, Horse set foot on soil. Real soil. The scent’s origin. The draugr dismounted and fell to his knees. Little blades of grass grew from the dark, soft earth under Horse’s hooves.

‘Look, Horse,’ the draugr said. ‘Grass. Real, green grass.’

His eyes had long since dried up, but inside his hollow chest, the draugr wept. Horse nudged the grass with her muzzle but said nothing.

‘We should turn around,’ he said, finally, the witch’s words ringing in his mind. ‘If something — someone — is still alive in this fjord, it might be we who bring their deaths.’

Horse took them back east, keeping the water on their right-hand side. Soon, the gale howled at their back again.

In the early evening, the draugr pulled the reins. Warm air smelling of rich soil and grass caressed his face as though the icy gale had never existed.

‘Horse,’ he said. ‘The fjord is on the wrong side.’

Horse flicked her ears, confused.

How had he failed to notice that the angry waves roared at his left and not his right? For how long had they been travelling in the wrong direction?

‘What is this witchcraft?’

He swung Horse around and continued up the fjord, east and away from any potential living things. For the first time in a generation, he urged her to a trot.

In the hour after midnight, the ghost ship appeared on the water again, shredded sails whipping in the opposite direction to the wind. Again, the shadowy vessel exposed its missing stern and set course out west, where it vanished.

Had the draugr been alive, he would have shuddered.

They kept going through the night, watching the fjord on their right and the mountain on their left. Morning came and the icy wind whipped at their back. But the next evening, he found they had once again been travelling with the fjord on their left. Somehow, they had turned around and gone back west, towards the warm winds and the earthy scents.

He dismounted and yelled at the Aesir, shaking his fist towards the sky and the sea. Everywhere, he saw signs of life. Grass growing, tree saplings sprouting, insects buzzing.

In this hidden-away fjord, life had prevailed. And on the brackish water, the ghost ship sailed, warning of death to come. He glanced around, nervously — an emotion that had not touched him for decades — and once again turned Horse back inland.

When night fell, the clouds had grown so thick, the fjord cowered under a compact shadow. The ghost ship came and went.

The veil of dawn lifted and with the increasing light, a landscape took form. The soft soil by the shore held fields of oats and barley. Early-rising sheep ran across the road before him, their bells clanging, and log cabins clung to the green slopes under the mountainside. The road changed from the hard, grey surface of rough gravel into a muddy path with wheel tracks on both sides, and in the middle, a deep furrow of hoof prints. Horse’s hooves thumped softly against the wet earth; a sound as strange to the draugr’s ears as the warm air against his face.

Once again, they had been turned around.

‘Thrice we have seen the ship, and thrice we have turned back. Yet here we are, once again, going in the wrong direction.’

Horse did not reply, but she did slow her steps.

‘No, let us continue,’ he said. ‘We cannot seem to escape this valley, so we may as well see what awaits us at the end.’

Rich fields and fat livestock spoke of a land untouched by illness and blight; a bubble of life in a world ruled by Hel, the Aese of death.

‘A town,’ he said. ‘Horse, I see a town.’

The collection of houses proved to be only a village, but even as much as a single building was more than the draugr had seen in a lifetime. Here, farmers worked the fields, children played in the road, and chickens plucked at the grass between the houses.

The draugr watched this mundane yet miraculous display of life with a slack jaw. Horse carried him forward, ears pricked. Then, a farmer raised her head, dropped her tools, and screamed. Another farmer joined in. Soon, the whole village filled with the sound of panicked voices.

The villagers ran. They ran like he had run and his wife had run and their neighbours had run. He was a dead man on a dead horse, entering the turf of living, breathing people.

A young man picked up a child and headed for the fields. A middle-aged woman herded a flock of toddlers into a house and slammed the door.

The draugr sat motionless in the saddle, stunned by the unreal scene that played out before him.

‘Horse,’ he said, and his voice caught. ‘I recognise this place after all. I don’t know how I could forget it.’

That small, grey cabin on the tongue of land had been his grandmother’s. The whitewashed house at the base of the mountain had been his father’s. And a tarred timber structure beyond the next curve of the road would be the house he had built with his own two hands.

‘This is where I came from. This is where I grew up.’

This was where, once, a dead man had ridden into the village and only an ageing witch had challenged him.

‘There is the witch’s hut,’ he said, and as though summoned, the white-haired crone stepped out. Ladle in hand, she called on the power of the gods. Her spells took physical form; like a cloud of insects they swirled around him.

The draugr bared his teeth in anguish.

‘I am he,’ he whispered. ‘I am the draugr from my youth. How is this possible?’

The witch’s spells assaulted him; a force unlike anything he had ever encountered. But one person’s words would not stop him. Horse continued her steady walk, her ears laid flat. He braced himself, leaning into a wind of curses, but that’s all it was.

When the witch’s neighbour came out of his house and joined her, he did not react. When two more stepped out and shouted vile things, he looked up. Only when people began to emerge from the woods where they had hidden, did he frown. This had not happened last time.

The witch shook her ladle and yelled words he could not hear. The crowd shouted in response. Angry villagers poured out of hiding places, high and low. And then they were upon him. They pulled him out of the saddle, ripped the clothes off his body, tore the flesh off his bones. He had a glimpse of a familiar face in the crowd — the face of his own young self — before a spade hit his face and he saw no more.

The chanting voice of the witch carried through the ruckus.

‘If the dead ride unchallenged through the land, then Death shall unchallenged claim the people.’

The draugr turned his head towards her voice and listened.

‘But on my watch, the dead shan’t pass unchallenged and Death shan’t claim my people.’

Unchallenged.

Everything fell into place. The words she had spoken in his youth rang true. She alone had defied the rider, and she alone kept her people safe. But once she was gone, Hel had taken them all.

‘Horse,’ the draugr said through broken teeth. ‘The fates the ghost ship foretold are not the villagers’, but our own.’

‘Yes,’ said Horse, her voice soft and deep. ‘This time, we die. And your people live.’

Short Stories

0 Comments